How one college student with invisible illnesses navigates academics, work, and the constant pressure to “push through” life and its many struggles and demands.

Most mornings, I wake up feeling like I’ve already lived an entire day. My body is perpetually tired; my feet haven’t even touched the floor yet. The pain in my body aches deep in my bones; my muscles are tight; my back will hardly bend. Sleep cannot fix me—I can’t manage to stay asleep long enough to get rest that repairs my aches and pains. We won’t even get started on the very vivid night terrors, which often have me reliving some of the worst moments of my life night after night. My brain feels foggy, like it is being stitched together with threads so thin they can hardly hold my thoughts steady. Still, I have to get up. I need to go to work. Schoolwork beckons to me from my office across the hall from my bedroom. I go to work and give it my all, even though I feel like I walked in running on empty. I make a difference with a smile on my face. I get recognized for my department—which I work and run all by my lonesome—making #2 in sales in the entire company the week before Thanksgiving, #1 the week of, and #3 the week after. Pretty good stats. I am proud… and I am exhausted. I go home on fumes that I’ve been stoking since my alarm went off this morning. I still have chapters to read, quizzes to take, discussions and papers to write. I sit at my computer, and my eyes flutter closed while I try desperately to read this week’s lesson. This is the rhythm of living with chronic, invisible illness as a college student: you continue to perform long after your body begs to stop.

The expectation to “push through” becomes so ingrained that you stop recognizing it as a choice. It becomes an automatic activity in your everyday, as easy and routine as breathing. You hide your tiredness, your pain, your discomfort; you put on this façade in front of other people, because “you’re too young to be this tired” and “you’re too young for your back to hurt.” Beneath the layer of practiced normalcy is a body constantly negotiating what it can and cannot accomplish today, plus a mind carrying crippling guilt of falling short on both sides.

Researchers Karly Ball Issacson and Elizabeth Tuckwiller (2025) attest that college students with chronic illnesses face significantly heightened emotional challenges. Their study found that these students “experience higher rates of anxiety, depression, shame, and loneliness compared to their peers not experiencing chronic illness,” and that these mental health patterns shift depending on the type of illness. In other words, the burden is universal no matter the degree of struggle.

Invisible illness is isolating by design. People can’t see that your body is attacking you from the inside out; as a result, the legitimacy of your experience is constantly under scrutiny—not only by others, but by yourself, as well. You become so tired of fighting this constant battle of being seen that you start to question yourself: Am I weak? Am I just complaining? Am I not trying hard enough? When other people cannot see your pain; when professors cannot see on a measured scale your level of fatigue; when coworkers watch you perform (or underperform) your tasks without understanding the cost, you start to doubt your own reality. These thoughts are dangerous… and ironically enough, it can make some illnesses even worse.

I live in a constant state of depletion. Achieving notable things like a high GPA and President’s List does not make my symptoms less. I have fibromyalgia. I have chronic pain. I have chronic fatigue. I have severe PTSD. I have depression. Hell, I’m 30, and have suffered from insomnia for twenty years. Some days I can’t even remember what I was about to say mere seconds before; after all, I have a traumatic brain injury on top of everything else. I have learned throughout my lifetime to hide my ailments; people cannot fathom the pain I feel each and every day, or the constant battles I fight within my mind from the traumas of my past. People can only see my accomplishments, my success—not the sacrifices I make every day, like choosing to work and not having the capacity to cook for myself once I get home, or choosing to shower and having to take a break afterwards because of feeling so weak and shaking so badly. The outside world sees the deadlines met, the tasks completed—but never the flare-ups that I know are coming because of choosing to push through and get things done. You learn to function until you crash. Then, you muster up enough recovery to function all over again. The cycle repeats itself day in and day out. Rest is not restoration; it is damage control.

To be blunt, I envy some of the most minute things about the lives being lived around me. On campus, I watched students casually stroll to their next class while I had to take breaks to breathe and stop shaking. I hear the gossip at work about me working slower some days, and have to keep my composure because I know no one could understand the price I pay to do every single thing. Sometimes I just want to go put my heartrate data in their face to show them the exertion it takes for me to do simple things. In those moments, I just have to shake my head and laugh. They notice far more the moments I’m not going 100 mph, but forget to acknowledge my outstanding performance metrics that span company-wide. See how that works out? Convenient.

The quiet shame attached to chronic illness has gained some type of normalcy, which Issacson and Tuckwiller highlight in their findings. Shame for slowing down. Shame for missing a day of work or missing a class. Shame for leaving work early. Shame for backing out of or declining plans. Shame, shame, shame for the days where you simply cannot push anymore. And, oftentimes, shame for needing rest in a culture that is hellbent on treating exhaustion as a virtue. We glorify overwork, late nights at the computer or office, and caffeine-fueled study marathons. No one glorifies the worker who prioritizes their health by taking a day for mental or physical rest. No one glorifies the student who needs a nap between a 12-hour work shift and 8 hours of class just to be able to think straight (thanks Professor Hammock for letting me sleep in your 8 am class, what a gem). No one acknowledges the emotional weight of managing disability accommodations that may or may not actually accommodate.

I cannot count how many times I’ve heard “but you don’t look sick,” is if that is a compliment; as if invisibility is proof of mental or physical wellness. As if the hours, days, weeks I spent recovering behind closed doors and closed curtains didn’t exist merely because someone else didn’t witness them. There are days where crawling out of bed feels like a victory. There are days where the brain fog feels so thick that reading one paragraph of a chapter feels like I conquered the novel Don Quixote. If I pass out in the shower; if I puke up blood; if I can’t walk from one room to the next without needing a break, assignments are still due. Bills are still due. Work still requires my presence tomorrow. Invisible illness does not pause for college or work or adult responsibilities. Feeling like I can’t achieve the simplest of tasks in a day can feel pretty crippling. The double-edged sword there is that the stress, in return, just makes me sicker. Ha! What a time to be alive. Perhaps one of the most painful parts of it all, is how utterly lonesome it can feel sometimes. I’m angry at my body for not cooperating, for sabotaging my success or my hopes or my goals or my dreams. My mind and my body are exhausted.

Chronic illness teaches you to minimize your needs because they feel repetitive. The symptoms will always return, and the excuses begin to sound the same. The apologies become meaningless. Yet disability research makes one thing abundantly clear: students with chronic illness are statistically more vulnerable, not weak. Our struggles are not excuses; they are our realities. Our resilience is lonely, exhausting, and yet necessary. Every day we choose what to sacrifice in place of making other things possible. We constantly decide between pain and productivity, between rest and responsibility. We are running on empty—it has become our lifestyle. We may still excel academically, and graduate with honors, and impress our bosses. We persist despite the absence of energy or strength.

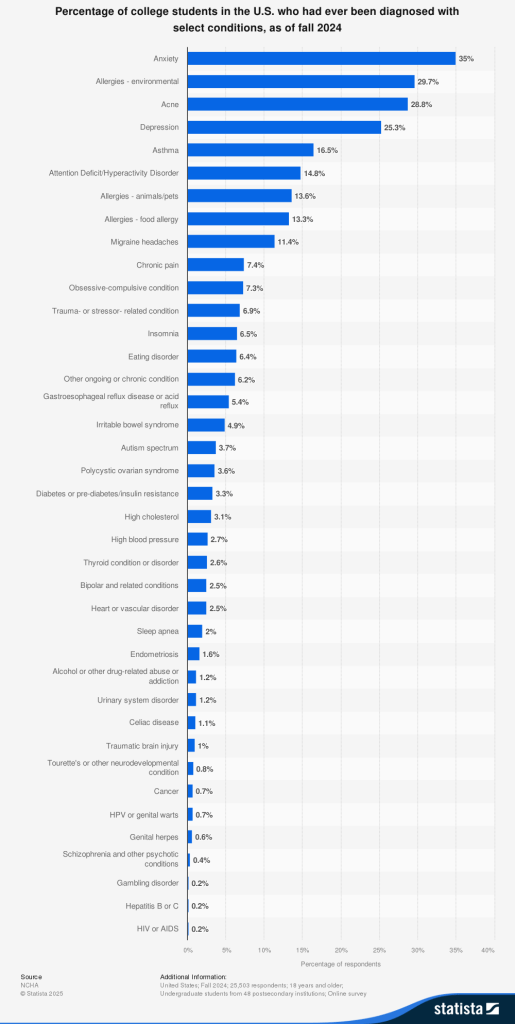

This infographic resonates with me heavily; I have been diagnosed with 15 on this list alone: anxiety, depression, asthma, ADHD, food allergy, migraines, chronic pain, OCD, PTSD, insomnia, other chronic conditions, high blood pressure, thyroid disease, endometriosis, and traumatic brain injury (TBI)

Leave a comment